A Diné History Of Navajo Weaving

The Navajo story of Spider Woman and her role in the origins of Navajo textile design.

Spider Woman

Spider Woman is a Native American deity recognized by many tribes across the Americas. One of these tribes is the Diné (Navajo), by whom Spider Woman is called Na'ashjé'íí Asdzáá. When herself and Spider Man (Na'ashjé'íí Hastiin) came into the third world, Nihaltsoh, the Holy People foretold that Spider Woman would weave a map of the universe and constellations. One day, while foraging and exploring, Spider Woman touched the branch of a young tree with her right hand. When she lifted her hand, a string was spun from the center of her palm. She tried to detach the string by spinning it around the branch, but in doing so, she created a beautiful web. She detached the string with her left hand and knew this was the weaving the Holy People were speaking of. She spent the rest of the day creating new shapes and patterns on the tree branches.

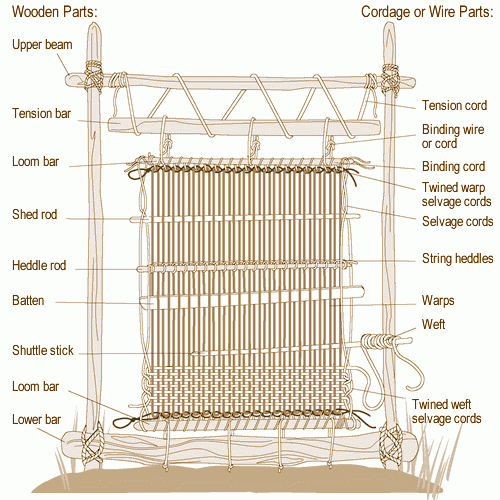

The Holy People visited Spider Woman and Spider Man to teach them how to create a loom, and the songs to sing to create a strong loom. The upper beam was made from Sky, the lower beam was made from Earth. These beams would support the weaving. The warp strings were made from sun rays, to serve as the weft foundation. The heddle from crystal and lightning, to preserve the fibers. The comb was made from white shell, to clean the strands as it combs. The battin was made from a sun halo, to seal the weaving.

The wise construction of a loom, the skill of weaving, and the prayer songs would all be taught to the Diné by Spider Woman and Spider Man. Spider Woman reappears throughout Diné storytelling. She helps the twins Monster-Slayer and Born-Of-Water find their father, the Sun. She is said to live on the top of Spider Rock, in Canyon De Chelly, AZ. There is a story of a young Diné child, who was spotted and chased by an enemy. The child ran throughout the canyon, searching for a place to hide when a strand from atop the Spider Rock was presented to him. Spider Woman had saved the child. Although it is said that parents tell their children to be obedient with this cautionary tale: Spider Woman eats the naughty children and leaves nothing but bones, hence the white strip at the top of Spider Rock! Many weavers rub their hands with the web of a spider before starting a project, the same practice is used on newborn children when their parents hope they will grow up to be great weavers.

No matter her role in the story, Spider Woman's reputation of being a savior of the Diné is not misearned. With her teachings of weaving she brought forth the original idea of the Beauty Way, Hozho. She has helped the people survive again and again- with her teaching being an essential part of what keeps many Diné alive today.

Diné Weavers

The Diné way of life incorporates many different art forms, such as pottery, jewelry making, basket making, weaving, sand painting, and much more. These arts and crafts were not typically made for purely artistic means but were used for various daily and spiritual practices. Diné weavers created clothing, blankets, and rugs for their people to stay warm and comfortable. The process of making a weaving could take a few weeks to a few years to complete, with various factors such as size, materials, and design contributing to the required time to complete a weave. Each project was as unique as the weaver, as it is traditional to not think out or draw your design, only to keep the details in your head and let the weaving come out naturally. There are only a few consistencies in Diné weaving. They typically have no fringe, and if the pattern has a border, it is traditional to leave a break on the edge, so that the pattern isn't trapped along with your talents and mind.

Before the introduction of the Churro sheep by the Spanish conquistadors, Diné weaving consisted of cotton that had been traded up from Central America, and things like shoes and baskets were made from fibers of plants and hair. In the 1500s, Spanish conquistadors brought sheep and wool, which were traded and distributed among Native American tribes, not only the Diné. Another tribe famous for their weaving is the Pueblo, which is believed to have shared their knowledge of weaving with the Diné by some historians and theorists. These Native weavers were not only weavers but shepherds, carters, dyers, and spinners of yarn.

Many years later, during the 1800s, the Diné would begin to trade and sell their weavings with the settlers. The rareness included with each weave, created by invested time, rare material, and possibly the mythical otherness of being a Native American and history of looting, created a huge market for the weaves. The consumers dubbed them “Chief Blankets”, which was ironic as the Diné did not operate under a Chief system. This crucial time in the 1800s paved the way for the large market demand for Navajo weavings today.

Today, many Diné weavers weave as a career. It is still common to shepherd your own sheep, or create your own yarn from wool, and not uncommon to buy the products premade (either locally made or not). Before, the typical weaver was a woman who was considered a valuable wife. Now both women and men weave, with no promise of marriage involved. Their numbers as weavers have lowered, but the art form is far from being dead. This could be due in part to the modern-day market for the ‘Chief Blanket’. The American southwest is still a strong trading post for Native American arts and crafts. Some weavers struggle to find that balance of western capitalism and Indigenous values, but it is most certainly there.